Confessions of a Blogagogue: Rethinking Cultural Studies, Technology, and Composition by Marcy Leasum Orwig

Abstract: The field of cultural studies has a long and varied history. It was estab-lished in the 1930s by scholars associated with the Frankfurt School. The tradition was continued by Stuart Hall and others at the Birmingham School of Cultural Studies in Great Britain. By the late 1980s and early 1990s, the field of study exerted an important influence on American composition theory and practice. Today, a re-newed interest in cultural studies is linked to the use of technology. Scholars such as Steve Jones and Stephanie Kucker (2001) discuss how “we [should] examine the Internet as another media technology situated in routine social practice and every-day life†(212).  But are the recent interpretations that link cultural studies to tech-nology justified? This article argues that such interpretations are justified and uses cultural studies as a way to rethink a specific aspect of new communication tech-nology: the current phenomenon of the blogosphere.  More specifically, this article will focus on whether or not students can apply critiques to culture through an eth-nographic study of composition blogs and will end with the implication of how new “democratic†technology can still potentially reinforce a hegemonic perspec-tive.   .

Introduction: Computer Technologies and Student Awareness of Culture

Cynthia Selfe and Susan Hilligoss, in Literacy and Computers, explain that scholars in the field of rhetoric and composition need to understand “how computer technologies, literacy, and culture are connected†(13). This statement puts into perspective the focus of my article.  I am most interested in how computer technologies, literacy, and culture combine to influence composition pedagogy.

Specifically, I am skeptical of the idea that computer technologies will automatically increase student literacy and their awareness of culture. As Clayton Pierce states, “Historically, technology within the sphere of educa-tion has always been a means by which to shape and enhance the transmis-sion of knowledge and information . . .Yet this relationship between educa-tion and technology has in official policies also been one of passivity and adaptation†(131).  Pierce’s point might seem pessimistic, but I agree with him that the acceptance of technology in education needs to be actively dis-cussed.

For example, overly optimistic statements like the following one by Mark Poster in “Consumers, Users, and Digital Commodities†is, for me, troubling: “In blogs, massively multiple online games, and peer-to-peer file-sharing programs, consumers are transformed into users, creating content as they download it.  In these contexts, the passive individual consumer of mediated industrial capitalism evaporates, and new figures of mediated practices are born†(249).  While I agree that students (as consumers) are often transformed into users, I disagree that the idea of capitalism will “evaporate†with the use of new technology. To further understand the topic of computer technologies, literacy, and culture, I begin my article with a short historical disciplinary context of cultural studies theory.

Disciplinary Context of Cultural Studies: Beginnings of Cultural Studies in the Composition Classroom

Cultural studies first emerged in composition theory and practice in the late 1980s and 1990s.  Diana George and John Trimbur explain in “Cultural Studies and Composition†that the Reagan-Bush years prompted a sense of urgency about the rightward direction of the country with its “back to ba-sics†attacks on the “permissive†1960s.  Such a political turn in rhetoric and composition can be seen, according to George and Trimbur, by the late 1980s in a new emphasis on multiculturalism, the politics of literacy, and the implications of race, class, and gender for the study and teaching of writing (72).  In particular, James Berlin in Rhetorics, Poetics, and Cultures (1996) argues that it is impossible to separate literary and rhetorical texts from political life.  He states, “As the lived experiences and everyday lan-guage of citizens become more and more diversified . . . It is no wonder that the meaning of culture and its role in English studies are urgent issues to-day†(xx).  Later, Berlin presents his concept of “social-epistemic†rhetoric within refigured English studies.  He explains, “Social-epistemic rhetoric is the study and critique of signifying practices in their relation to subject for-mation within the framework of economic, social, and political conditions†(77).  Berlin acknowledges that such a concept is dense, but later explains the central role of ideology in the framework.  In other words, a social-epistemic rhetoric studies and critiques cultural signs and ideology in rela-tion to conditions based on the economy, society, and politics.

Cultural Studies in the Composition Classroom Today

Today, scholars such as Bruce McComiskey in Teaching Composition as a So-cial Process urge “writing teachers to incorporate social-process methodolo-gies into their existing composition curricula, not neglecting the linguistic and rhetorical levels of composing, but rather strengthening and reinforcing them with attention to the social contexts and ideological investments that pervade both the processes and products of writing†(134).  In other words, he encourages composition instructors to use cultural studies in their class-rooms, and he offers an example of rhetorical inquiry and cultural studies methodologies with his cycle of cultural production, contextual distribution, and critical consumption.  For the first part of this cycle, cultural produc-tion, he believes that students need to understand ways in which individu-als inscribe texts with “preferred readings†(25).  The second part of the cy-cle, contextual distribution, helps students examine the connection between context and culture.  In the third part of the cycle, the analysis of cultural values produced in texts and their “distributing media to the subjectivities who encounter the produced and distributed values†comes to the fore (29).  With new advances in communication technology, McComiskey argues that it is more important than ever for composition instructors to use such frameworks to show students how to critique culture.

I strongly agree with what McComiskey is calling for, and using cul-tural studies in composition pedagogy is, as Berlin also argued, an impor-tant undertaking for instructors.  Indeed, Nick Stevenson in Cultural Citizen-ship contends, “From the importance of ‘culture’ in determining the com-petitiveness of the modern economy, to the increasingly symbolic nature of political protests, we are currently living within a cultural society unlike any other†(16).  However, not everyone agrees with such a stance.  For ex-ample, during a 1997 College Composition and Communication Conference (CCCC) roundtable response to Berlin’s work, Susan Miller worried that “the content of such courses is not writing—is not persuasion to assume the positions of those whose acts of writing are interventions.  Nor is it system-atic demonstrations of how to write—not ‘well,’ but powerfully, to subvert . . . conventional subject positions†(499).  In other words, Miller is concerned that writing courses rely too heavily on cultural studies critiques.  Further, Diana George and John Trimbur respond to her in “The ‘Communication Battle,’ or Whatever Happened to the 4th C?†by writing, “We are sympa-thetic to Miller’s concern that media analysis, or more generally what’s be-come known as the ‘cultural studies approach’ to teaching writing too often winds up being a hermeneutic rather than a productive activity†(696).  The problem of using cultural studies in the composition classroom stems, I think, from the fact that cultural studies did not originally come from the field of rhetoric and composition.

The Background of Cultural Studies

Henry Giroux has called on instructors everywhere to include cultural stud-ies in the classroom.  He writes that “Culture now plays a central role in producing narratives, metaphors, and images that exercise a powerful pedagogical force over how people think of themselves and their relation-ship to others†(62). For this reason, Giroux argues that cultural studies connects knowledge to everyday life (meaning to the act of persuasion), schools and universities to broader public spheres, and rigorous theoretical work to effective practice that students can use in their relationships with others and the larger world (66).  Giroux explains, “This seems especially important at a time when new electronic technologies . . . as a primary edu-cational force offer new opportunities to inhabit knowledge and ways of knowing that simply do not correspond to the longstanding traditions and officially sanctioned rules of disciplinary knowledge or of the one-sided academic emphasis on print culture†(67).  While Giroux is certainly a pro-ponent of cultural studies, he also discusses some problems with using it as a pedagogical framework.  For example, he argues that it is often too far removed from other cultural and political sites where the work of public pedagogy takes place (71).  However, he asserts that cultural studies is about “Stepping out of the classroom and working with others to create public spaces where it [cultural studies] becomes not only to ‘shift the way people think about the moment, but potentially to energize them to do something differently in that moment,’ to link one’s critical imagination with the possibility of activism in the public sphere†(77).  While Giroux presents captivating and inspiring scholarship on cultural studies, he doesn’t give specific examples of how it might be used in the classroom.  His lack of concrete examples of how it might be used in the classroom for interactive student learning is due, in part, I think, to the very beginnings of cultural studies and its inception by highly theoretical intellectuals.

The Frankfurt School of Cultural Studies

The first work in cultural studies was done by a group of German intellec-tuals.  These scholars included, among others, Theodor Adorno, Max Hork-heimer, and Herbert Marcuse who were collectively associated with the Frankfurt School.  This school was established in 1923 and following the coming to power of Nazism in Germany in 1933, it moved to New York.  John Storey in Cultural Consumption and Everyday Life explains that, “The experience of life in the United States had a profound impact on the School’s thinking on the production and consumption of culture†(19).  For example, Adorno wrote about the culture industry in 1944, and his work critiques the emergence of mass media like films and radio.  He states:

Amusement and all the elements of the culture industry existed long before the latter came into existence. Now they are taken over from above and brought up to date. The culture industry can pride itself on having energetically executed the previously clumsy transposition of art into the sphere of consumption, on making this a principle, on divesting amusement of its obtrusive naivetes and improving the type of commodities.

In other words, Adorno claims that mass media are culture industries that manipulate the population into consuming widely produced messages.  These messages are then spread using technology, and here is where Her-bert Marcuse had his greatest influence because he relentlessly studied the role of technology and its impact on civilization.  Marcuse saw technology as anything but neutral as it contributed to and accelerated the decline of the individual’s potential for achieving a critical perspective concerning the existing conditions that constitute advanced society.  For example, he wrote that dissent against the status quo in such a context fades into the back-ground through the increased importance that technology plays in the pro-duction process of the technological society (11).

The Frankfurt School Continues with the Birmingham School

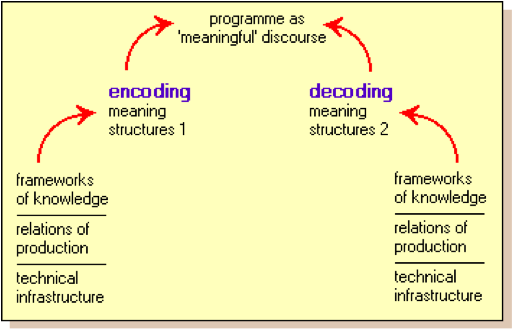

The tradition started by the Frankfurt School was continued by the Birmingham School of Cultural Studies.  In particular, Stuart Hall’s “Encod-ing/Decoding†(1973) proposed a model of mass communication that em-phasized the importance of active interpretation of messages in his “circuit of communication†(see figure to the right - Hall’s “Encoding/Decoding” [1973]).    Within this circuit, he explains that there is a progression from encoding (producing messages) to the actual discourse (the published text or broad-cast) to finally decoding (consuming messages).  Hall claims that mass communication is given to a diverse audience which then reacts diversely to the original message. He names three distinct categories of reactions: domi-nant (i.e. hegemonic view), negotiated (i.e. bargained view), and opposi-tional (i.e. counter-hegemonic view).  I will explain these categories in more detail later in my article when I analyze student writing.  While these cate-gories are helpful, Hall warns against an oversimplification of the audience reactions.

Within this circuit, he explains that there is a progression from encoding (producing messages) to the actual discourse (the published text or broad-cast) to finally decoding (consuming messages). Â Hall claims that mass communication is given to a diverse audience which then reacts diversely to the original message. He names three distinct categories of reactions: domi-nant (i.e. hegemonic view), negotiated (i.e. bargained view), and opposi-tional (i.e. counter-hegemonic view). Â I will explain these categories in more detail later in my article when I analyze student writing. Â While these cate-gories are helpful, Hall warns against an oversimplification of the audience reactions.

Extending the Cultural Studies Conversation

Hall’s article deals mainly with analyzing television discourse, but can his concepts of encoding/decoding also apply to new communication tech-nologies?  As mentioned earlier, McComiskey urges composition instructors to apply cultural studies to new technology.  Similarly, Pamela Takayoshi (1996) and Barbara Blakely (2000) also use Hall’s categories to analyze com-puter literacy. So, in order to extend this conversation, I present a sample analysis of one particular aspect of technology: the blogosphere.

The word blog was first used in 1997 to describe journalistic entries put on a personal website. Today, maintaining a blog is quite easy since there are interactive websites that allow anyone to do it: All you need to get started is a name, a password, and an e-mail address. Â The most popular of these blog websites is blogger.com, which was started in 1999. Â Its popular-ity is based in part on its ease of use and the fact that it allows users to per-sonalize their web addresses. Given the ease with which blogging can be practiced, the increasing popularity of the personal blog is not surprising. For example, today there is a proliferation of blogs and the blog search en-gine called Technorati recently found that 1.4 blogs are created every sec-ond of the day.

While there are many blogs, I will specifically analyze student blogs since my article has a pedagogical interest.  I, a self-proclaimed blogagogue, hope to begin a starting point for further conversation on the specific topic of student blogs while also encouraging composition instructors to think about how to best incorporate such blogs into their own classrooms.  As Cynthia Selfe and Gail Hawisher in Literate Lives in the Information Age write, “Culture plays a critical role in shaping values regarding the literacies of technology and that, at the same time, the literacy values and practices of people and groups also shape cultures†(126).  I contend that, within our field, this sentence sums up quite nicely why such further conversation is needed on the topic: at stake is cultural and rhetorical literacy for our stu-dents.

Encoding My Story: A Methodological Pun on Hall’s Theory

From a cultural studies perspective, one of the primary goals of literacy in-struction is to help students “read†the messages they receive from mass media. Interestingly, Hall notes that such a message must first become “a story before it can become a communicative event†(167).  So, to present my analysis of student blogs, I will “encode†the data into a “story.† My sam-ple of student blogs comes from my experience of teaching a foundation communication course with 26 students at a large Midwestern university from August to December 2008.

I conducted my research by using ethnographic methods in an effort to analyze student blogging in the form of a case study.  I realized that a qualitative approach would be useful in gathering the data for my analysis because, as Denzin and Lincoln explain, qualitative research situates “activ-ity that locates the observer in the world. It consists of a set of interpretive, material practices that make the world visible†(4).  Specifically, I needed a method that would render a discourse community “visible†for my analysis and student blogs certainly fit the definition of a discourse community as they generate conversation.  Ethnographic researchers have been “drawn to discourse communities in order to gain a better understanding of the mean-ings that community members generate through conversation†(LeBesco 63).  Although there are many different approaches to qualitative research, I chose to use phenomenology for my study, which Creswell defines as re-ducing “individual experiences with a phenomenon to a description of the universal essence†(58).  Phenomenology, then, seeks to describe what par-ticipants have in common as they experience a phenomenon.

The rest of my article will begin with my “story†of student blogs, where I explain how blogs were used in my classroom and how my stu-dents responded to the assignment.  The article continues by using Hall’s concept of decoding to analyze my “story.† I conclude with implications of applying Hall’s concepts to student blogs and what it might mean for in-structors of composition.

My Story: A Blogging Narrative

As I typed up the blogging assignment sheet, I had a hard time deciding what sort of topics my students should focus on.  Should I open it up to any topic?  Or, should I set a specific one?  Both options seemed viable to me, but I decided to ask students to blog about a topic related to all of their ma-jors: business.  By having my pre-business students write about this topic, my intent was that this would lead to them to write about some aspect of culture.  I also set a timetable so that my students wouldn’t procrastinate writing their five required blog entries.  I grouped these five required blog entries into three main rounds of blogging.  Since this was my first semester using blogs in the classroom, I wasn’t sure how it would go but I was curi-ous to see what would happen.    As the (fall 2008) semester progressed, I began to worry about having my students blog.  Unlike other traditional assignments where only I read their papers, their blogging would be available to anyone online.  As Selfe and Hilligoss write, “Writing that appears on a screen seems more public.  In contrast to the privacy of paper documents, the screen displays texts for all to see†(12).  Indeed, even though my students’ blogs would be marked as private, the potential for others outside of our class to haphazardly come across them and read what my students had written was still there.  Per-haps more important to me was the thought of what my students would blog about and how others would react to their blogging.  As my students progressed through the blogging assignment, I de-cided to project their entries onto the overhead screen during class and I had everyone share what they had written.  Not surprisingly, I found that most of my students were more vocal on their blogs than in a classroom dis-cussion.  For example, one student wrote what was supposed to be an analysis of a local Best Buy in town:

Being a Best Buy customer has a very good feeling because of the reputation that they have. They have one of the best productivity in the nation. Best Buy is very well known everywhere. They are basically an electronic store. They sell TV’s, stereos, and other house appliances.  The name Best Buy mean simply this: when buying products from them you get the “best buyâ€. I always think that when I go, I am getting the best buy when I buy the products.  Best Buy is my favorite place to shop for elctronics. I really encourage all my friends that are looking for appliances to go shop at Best Buy. Just like the name says you get the best buy when you are shopping for their products.

However, when I tried to get him to talk in class about his post on Best Buy, the discussion basically went something like this:

“Why did you choose this store?â€

“I don’t know.â€

“Well, you describe in your blog entry that you often go to this store.  Maybe this is why you chose it?â€

“Yeah, maybe.â€

And so on . . .

Most of the other students were the same way.  I would click on the stu-dent’s blog and up on the overhead screen there would be a substantive post about their chosen store.  However, when I tried to get them to talk about it in class, most of the students didn’t want to share.  Of course, even if they didn’t want to talk about their topic, I got them to talk eventually (however briefly).  Most of the students fell back on what they had written about in their post and so perhaps this made sharing a little easier.  I noticed that I would ask the student questions about the writing topic, but when I left it open for others to ask questions, there was silence.  With this experi-ence in mind, I wondered how they would be motivated to make comments on other each others’ blogs.

While the remaining student blog posts and comments, in general, were not very noteworthy, a good example from my class of a blog entry with corresponding comments came from one particular student who posted an entry about Mustangs (the car). Â He started his entry with some general background information such as when it was launched (April 17, 1964) and how much the car originally cost. Â He ended his entry with:

I have always wanted to drive a Shelby GT-500 Mustang. Â Its looks are a thing of beauty, this vehicle is a mans car. Â It featured special quarter-panel windows and rear air scoops on each side and an optional automatic transmisson.

I wasn’t expecting the rash of comments that his entry generated.  Within a day or two, his entry had generated eight comments.  It started with this one:

- Mustangs are one of my favorite cars. I have always wanted to drive on to. My friend had a musting but he sold. I wish i had the chance to drive one. Â Â Â Â Then it continued with others:

- ooohh man shes a beauty. do you have a Shelby? personally i kind of like the Cobras a little more, but the mustang is definitely a great car and have made some awesome body styles over the years.

- I have wanted a mustang since I started playing with barbies.

- I personly think mustangs are poorly made…

- Really I thought that the car was named after a horse. I personally like mustangs because of the design of the car.

- I love Mustangs too. My friend had a white mustang and we were going out to eat somebody ran a red light and hit us. It didnt make it through.

- I always wanted a mustang for some reason. I think that it’s because they have so many styles and designs.

- Mustang is pretty much every teenage boy dream. All you think about is taking a girl out, or racing it. I will love to own a mustang. Its like a need, just like peanut butter and jelly.

After reading this student’s post and the following comments about it, I wondered if my students were going in the right direction with blogging.  In other words, I had imagined a very different response to the blogging assignment and perhaps I was too idealistic in thinking that they would just automatically assume a critical eye when using the technology.

To be fair, I had asked them to just write about business topics and I had not prompted them to think critically. Â Another example of a student entry demonstrates the lack of a critical eye:

In an article i read, it talked about how blackberry is coming out with a new phone, The Storm, which is supposed to be the  competitor against iphones. The storm is said to be a better business phone over the iphone. i personally have a blackberry. I have the blackberry pearl through sprint. Blackberrys are compatible with many different carriers such as, at&t, t-mobile, verizon, and sprint. When at&t got their hands on the iphone and know that they are the only carrier to have the iphone, the other carriers decided to come up with a new phone to compete against it. Verizon made the dare and sprint made the instinct.

This particular entry had only one comment:

I think that its really good that blackberry is making an all touch screen phone. I love blackberrys and touch screen makes it even better! Indeed, it seemed like all my students were doing was writing about big box corporations, whether or not they liked Mustangs, and how cool the touch screen is on a blackberry.

Decoding My Story: Reactions to My Narrative

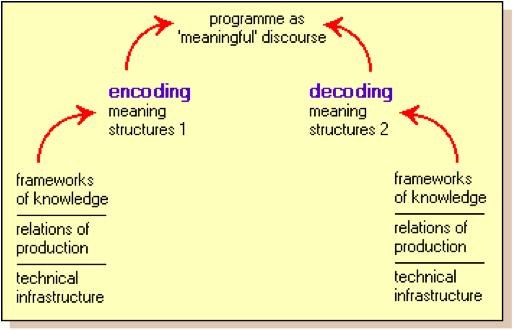

While there could be many different reactions to my “story,†as Hall would argue, I will present a decoded version of my reaction here (see figure - Hall’s “Encoding/Decoding Updated).  To begin, as mentioned earlier, his concept of the “circuit of communication†describes how messages are produced and then understood. For example, in the first part of the circuit (encoding) Hall was concerned with how mass media produce messages.  But, in the case of student blogs, instead of mass media it is the student who produces the message.  For example, the student who wrote about Mustangs “encoded†his message by implying that it is a “man’s car.† Second, in the circuit, is the actual discourse (i.e. a book, an article, a television broadcast, etc).  However, technology such as blogs makes producing a message so easy that all this student had to do was hit the “publish†button on his computer.  At that moment, his post was able to be seen not only by the audience of his classmates, but also by anyone else who stumbled across it.  The last part of the circuit deals with decoding, or consuming, the messages that mass media give us.  With the example blog post, the student’s original meaning was certainly decoded by his other classmates.  In fact, we see a diverse reaction from the implied meaning of a Mustang to be a “man’s car†to the other meaning of a girl wanting one ever since she was “playing with Barbies.â€

produced and then understood. For example, in the first part of the circuit (encoding) Hall was concerned with how mass media produce messages.  But, in the case of student blogs, instead of mass media it is the student who produces the message.  For example, the student who wrote about Mustangs “encoded†his message by implying that it is a “man’s car.† Second, in the circuit, is the actual discourse (i.e. a book, an article, a television broadcast, etc).  However, technology such as blogs makes producing a message so easy that all this student had to do was hit the “publish†button on his computer.  At that moment, his post was able to be seen not only by the audience of his classmates, but also by anyone else who stumbled across it.  The last part of the circuit deals with decoding, or consuming, the messages that mass media give us.  With the example blog post, the student’s original meaning was certainly decoded by his other classmates.  In fact, we see a diverse reaction from the implied meaning of a Mustang to be a “man’s car†to the other meaning of a girl wanting one ever since she was “playing with Barbies.â€

These diverse reactions fall into Hall’s three distinct categories of read-ing (as explained earlier): dominant (i.e. hegemonic view), negotiated (i.e. bargained view), and oppositional (i.e. counter-hegemonic view).  In the case of the Mustang blog entry, we could view the comments of it as a “man’s car†and “every teenage boy’s dream†as dominant, or hegemonic.  Other comments are harder to classify, such as the one discussing how they thought it was named after a horse or how they ran a red light which re-sulted in a smashed Mustang.  But, the one comment by a girl wanting a Mustang since she was “playing with Barbies†could be, I think, considered negotiated because she had a different reading of the original message.  While these reactions are interesting, what I find disheartening is that none of the students openly questioned the reputations of Best Buy, the value of a high-end car, or changing technology.

Differences between Traditional Cultural Studies and Today’s TechnologyWhat I find most interesting about all of this is that while Hall’s concepts still apply to the blogosphere, there is something else happening here as well. In other words, the concepts of encoding/decoding were originally focused on analyzing mass media such as television shows which were part of what Adorno would have called the “culture industry.†But what we have with the blogosphere is different in that there are fewer “gatekeepers.†For instance, bloggers can be anybody who is able to read and write (and who has access to a computer). They don’t have to be part of the “culture industry†the way a television producer or newspaper editor is. However, some might say that being able to read and write (as well as having access to online technologies) is now part of the culture industry.

Certainly Althusser, from a cultural philosopher’s point of view, would agree that students who learn to read and write become part of the workings of the culture industry. He asks, “What do children learn at school? They go varying distances in their studies, but at any rate they learn to read, to write and to add – i.e. a number of techniques, and a number of other things as well, including elements (which may be rudimentary or on the contrary thoroughgoing) of ‘scientific’ or ‘literary culture’†which are directly useful in the different types of production jobs.  He continues:

Thus they learn know-how . . . But besides these techniques and knowledges, and in learning them, children at school also learn the ‘rules’ of good behaviour, i.e. the attitude that should be ob-served by every agent in the division of labour, according to the job he is ‘destined’ for: rules of morality, civic and professional conscience, which actually means rules of respect for the socio-technical division of labour and ultimately the rules of the order established by class domination.

He concludes by explaining the “reproduction of labor power requires not only a reproduction of its skills, but also, at the same time, a reproduction of its submission to the rules of the established order†by reproducing the submission to the ruling ideology for the workers, and a reproduction of the “ability to manipulate the ruling ideology correctly for the agents of exploi-tation and repression, so that they, too, will provide for the domination of the ruling class ‘in words.’† For example, with the case of student bloggers, if students are taught that Mustangs are a “man’s car†and can then also read and write about it they are unconsciously reproducing the dominant ideology.  I’m sure that Ford would have loved this student’s post because, as marketers know, word-to-mouth advertising is the best possible form of promotion.

Follow-up to My Study

I asked my students at the end of the blogging assignment about their per-ceptions of the process.  So, a few weeks before their last round of blogging was due, I canceled one week of formal classes and held conferences with my students.  During conferences, I learned that a few of them had previous experience blogging. But, otherwise many confessed that the first blog entry was the hardest because they were unsure of what a blog actually was.  One student told me that I was “turning him into one of those people†he didn’t like.  In other words, he didn’t like bloggers and he felt like I was forcing him to become one.  But he mentioned towards the end of our discussion that he now doesn’t mind blogs as much.  Another student commented that he had “always heard about blogging, [but I] wasn’t sure how to do it, I like it [the blogging assignment] and the structure of topics.† Finally, one other student told me that she didn’t “like writing, but now [it’s] not so bad be-cause I like business topics, [I] wouldn’t have found [such topics] other-wise.† Similarly, another student told me that she never watches the news or reads newspapers and that now because of blogging she is forced to pay attention to such information.  She said she felt that it was a good thing be-cause otherwise she wouldn’t have cared.  Finally, one student shared that it helped him express his opinions when compared to writing normal pa-pers because he felt like he had a larger audience.  These comments made me realize two things.  First, my students were taking an active part in their learning process.  But, second, using technology (in the form of blogging) did not make that learning process automatically critical, as Poster suggests.

I think that my students have shown where the real work comes into play for instructors of composition who might use blogs in their own class-rooms. More specifically, my students have demonstrated that new tech-nology will not just make them critical thinkers, in fact, it may reinforce a hegemonic perspective. Instead, as composition instructors, we still have the arduous job of helping students see how culture affects their discourse while also helping them see that more “democratic†technology can still po-tentially reinforce a hegemonic perspective.  Therefore, I think this exten-sion of the conversation on cultural studies and new technology is impor-tant. As Selfe and Hilligoss note, “If computers require students to learn new habits of reading, they also change the way students write and think of writing†(14). More specifically, with new technology like the blogosphere, it is more important than ever for students to understand why they think in a particular way. Their ability to “read†culture is critical because otherwise they are just reproducing the same ideological stories.

Implications/Conclusion: Blogging in the Composition Classroom

Certain questions arise from my “story†such as “Are students able to apply critiques to culture through blogging?† and if so, “How?† I think, through my article’s discussion, that the answer to the first question is both yes and no.  As mentioned before, my students were able to write about business (an aspect of culture) but they did not apply any real critiques.  If I were to try this activity again, I would work to revise the assignment sheet to elicit more critical blogs.  My second question “How?†is much more difficult to answer because, as mentioned before, my students did not just assume a critical eye when using the new technology.  Therefore, it is here that there needs to be further conversation.

To continue the conversation, I argue that instructors need to find ways to help students understand the process of decoding and encoding in their own work. Â At this point in history, analyzing traditional mass media like print ads or television shows are useful, but so is analyzing writing that they can produce for a wider audience (such as blogging). Â I once heard that instead of mass media today, there is media for the masses. Â A survey con-ducted by Educause Applied Research (2007), shows the following facts:

- University students spend 18 hours/week on the internet

- Technology is first about communication for students

- Many students (59%) prefer a “moderate†amount of instructional technology in their courses

- Many students (60%) say instructional technology has improved learning in their courses

Such survey results show that, as Selfe and Hilligoss explain, “We see computer networks as a means for students to acquire literacy; that is, the networks can function as localized forums for acquiring the written literacy of a discourse community.  As students write, interpret, and negotiate texts via computer networks, they are participating within a context that pro-motes active learning†(89).  Thus, there is a real challenge that composition instructors have in incorporating technology into the classroom to help stu-dents analyze culture.

While I don’t have exact answers on how to help students analyze culture within the blogosphere, I hope my small study and resulting con-versation will encourage composition instructors to use and modify my ideas.  Also, I suggest here further resources for composition instructors to review and adapt into their own classrooms.  For example, George and Trimbur suggest two collections on how to integrate a more deliberate use of popular culture and media studies into the composition classroom with: Cultural Studies in the English Classroom (Berlin and Vivion, 1992) and Left Margins: Cultural Studies and Composition Pedagogy (Fitts and France, 1995). Additionally, they list textbooks associated with cultural studies including Rereading America (Colombo et al., 2007) which focuses on a series of dis-tinctly American myths and Reading Culture: Contexts for Critical Reading and Writing (George and Trimbur, 2006) which relies on semiotics to teach close readings of popular culture texts. George and Trimbur note that the popu-larity of cultural studies in the composition classroom may be attributed to the fact that the topics allow instructors to retain “two commonplace prac-tices: To begin student writing with a topic close to the self and to teach close reading and interpretation of texts†(“Cultural Studies†82).  All in all, I believe that using cultural studies in the composition classroom is impor-tant and can lead to students thinking about the possibilities of “democ-ratic†technology, such as blogs.

Appendix—Blogging Assignment Sheet

Writing for the Web: Class Participation Assignment

Introduction:

This assignment asks you to practice writing for the web by maintaining a blog through wordpress.com. Â We will be setting these blogs up in class. Â Only me, your instructor, and your fellow classmates will be able to view your blog. Â According to our textbook, Writing: A Guide to College and Be-yond, a blog is a source of public opinion (574). Â Keep this in mind as you begin your assignment.

Assignment and Purpose:

You will post (or put on your blog) a total of 5 entries where you will write about current topics in business. Â The first topic you will discuss will tie into your visual analysis paper. Â Other topics that you could blog about include other topics related to material we discuss in class or material that you dis-cuss in another business oriented class. Â Additionally, you can blog about current topics in business and these topics could be focused on something that you read in a magazine or newspaper, hear on the radio, or see on tele-vision. Â Also, you can write about a past experience you might have had in a business situation.

It is completely up to you what you will blog about.  But, remember that the point to blogging is to form an opinion about a topic and then write about why you feel this way.  By doing this type of exploratory writing, you will not only learn about business topics, but you will also practice writing.  As our textbook says, “Along with learning to write well, learning to think critically is the most important skill you will gain in college because your success in your professional and public life will depend on it†(12).

In addition to posting 5 entries, you will respond to your classmates’ entries by commenting on what they write about.  During the course of the semes-ter, you will make at least 5 comments.  Keep in mind that what you write will be seen by everyone in the class and that we will periodically look at examples from the class.

Planning:

As you think about starting this assignment, read pages 12-13 in our text-book.  Reading these pages will help you plan what you want to say in your blog entries.  As you post your blog entries, keep in mind the following out-line in addition to concepts discussed in class about what makes a “good†blog:

1. introductory paragraph explaining post

2. paragraph covering material you will discuss/blog about

3. paragraph with concluding remarks

Evaluation Criteria:

• Required amount of blog entries per semester (5 total, 5 comments)

• Blog entries demonstrate the thoughts and opinions of the blogger (you, the student)• Blog entries are on business topics

• The entries contain few grammar/spelling errors

• Blog entries refrain from profanity or inappropriateness

Schedule:

Thursday, Sept. 25 1st blog entry with three pictures of your sign/logo

Thursday, Oct. 23 2nd & 3rd blog entries on topics of your choice and also 2 comments on other blogs

Thursday, Dec. 4 4th and 5th blog entries on topics of your choice and also 3 comments on other blogs

By Marcy Leasum Orwig, Iowa State University

REFERENCES

Adorno, Theodor and Max Horkheimer.  The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception. 1944. <www.marxists.org>. Online.

Althusser, Louis. Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses. 1970. <www.marxists.org>.  Online.

Blakely, Barbara. “Critical Computer Literacy: Computers in First-Year Composition as Topic and Environment.†Computers and Composition 17 (2000): 289-307. Print.

Berlin, James. Rhetorics, Poetics, and Cultures: Refiguring College English Studies. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English, 1996. Print.

Creswell, John W. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design. London: Sage Pubs, 2007. Print.

Denzin, Norman K. and Yvonna S. Lincoln. “The Discipline and Practice of Qualitative Research.†Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry 3rd ed. New York: Sage, 2007. 1-43. Print.

George, Diana and John Trimbur. “The ‘Communication Battle,’ or Whatev-er Happened to the 4th C?†College Composition and Communication 50.4 (1999): 682-698. Print.—. “Cultural Studies and Composition.†A Guide to Composition Pedagogies. New York: Oxford U P, 2001. Print.

Giroux, Henry. “Cultural Studies, Public Pedagogy, and the Responsibility of Intellectuals.†Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 1.1 (2004): 59-79. Print.

Hall, Stuart. “Encoding/Decoding.†Culture, Media, Language. Ed. Stuart Hall, Dorothy

Hobson, Andrew Lowe and Paul Willis. London:Â Hutchinson, 1980. Print.

Jones, Steve and Stephanie Kucker. “Computers, The Internet, and Virtual Cultures†Culture in the Communication Age. Ed. James Lull. London: Routledge, 212-225. Print.

LeBesco, Kathleen. “Managing Visibility, Intimacy, and Focus in Online Critical Ethnography.†Online Social Research: Methods, Issues & Ethics Ed. Mark D. Johns, Shing-Ling Sarina Chen, & G. Jon Hall. New York: Peter Lang, 63-80. Print.

Marcuse, Herbert. The One-dimensional Man: Studies in the ideology of Advanced Industrial Society. Boston: Beacon, 1964. Print.

Miller, Susan. “Technologies of Self-Formation.†Journal of Advanced Communication 17 (1997): 497-500.  Print.

McComiskey, Bruce. Teaching Composition as a Social Process. Logan, UT:Â Utah State U P, 2000. Print.

Pierce, Clayton. “Democratizing Science and Technology with Marcuse and Latour.â€

Marcuse’s Challenge to Education. Ed. Douglas Kellner. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Pubs, 2009. Print.

Poster, Mark. “Consumers, Users, and Digital Commodities.†Information Please: Culture and Politics in the Age of Digital Machines. London: Duke UP, 2006. Print.

Selfe, Cynthia and Gail Hawisher. Literate Lives in the Information Age. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2004. Print.

Selfe, Cynthia and Susan Hilligoss. Literacy and Computers: The Complications of

Teaching and Learning with Technology. New York, MLA, 1994. Â Print.

Stevenson, Nick. Cultural Citizenship. Berkshire, England: Open University, 2003. Print.

Storey, John. Cultural Consumption and Everyday Life. London: Arnold P, 1999. Print.

Takayoshi, Pamela. “Writing the Culture of Computers: Students as Technology Critics in Cultural Studies Classes.†Teaching English in the Two-Year College 23.3 (1996): 198-204. Print.