Freaking the Mind: Exploring the Rhetoric of Magic in Criss Angel’s Mindfreak by Joseph Zompetti, Illinois State University

Abstract:

The art of magic has enjoyed increasing visibility and a resurgence of interest, as demonstrated by the rising popularity of magicians, such as David Blaine, Hans Klok, Franz Harary, David Copperfield, and the production of two major motion pictures within a single year – The Prestige and The Illusionist. With his number one-rated cable television show and his recent ten-year contract for a major Vegas show with Cirque de Soleil at the Luxor, Criss Angel  personifies the modern-day magician who is at the forefront of the magic renaissance. This paper attempts to examine the rhetorical potency of magic by analyzing the first season of Criss Angel’s award-winning television show, Mindfreak. By using Kenneth Burke’s concepts of symbolic action and identification, this paper explores the symbolic, albeit persuasive, dimension to magic as exemplified by Criss Angel.

personifies the modern-day magician who is at the forefront of the magic renaissance. This paper attempts to examine the rhetorical potency of magic by analyzing the first season of Criss Angel’s award-winning television show, Mindfreak. By using Kenneth Burke’s concepts of symbolic action and identification, this paper explores the symbolic, albeit persuasive, dimension to magic as exemplified by Criss Angel.

Introduction

Conjurers try to convey the impossible. They attempt to convince the audience that their performance is “real†magic. In the end, the magician is performing, just as an actor or musician would do, in order to convince the audience that what they are doing is not only entertainment, but also substantive – the illusionist wants us to believe and feel their act is occurring and is realistic. Although we know the “magic†on stage doesn’t actually happen – the assistant can’t disappear and the levitation is not within the realm of possibility – we still see, feel, and believe that what occurs on stage is real. That is the magician’s trade; it is the cornerstone of persuasion. We may think that sales persons, lawyers, and clerics are the masters of persuasion, but in “reality,†magicians are the foremost experts of persuasion. They not only entertain us, but they also reveal to us what is not real. They perform what we know is impossible. In effect, they sell us a bill of goods that we know we shouldn’t buy; thus, magic’s persuasive charm. According to Devant, a famous magician from the early 1900s, magic is “the feeling that we have seen some natural law disturbed†(p. 8). And as Aristotle remarked over 2,000 years ago, the “available means of persuasion†is what we know as “rhetoric†(Aristotle, p. 36). As a result, magicians are the modern rhetoricians, keen on persuading the rest of us that what is going on is really happening, when in actuality, the occurrence is nothing more than, literally, smoke and mirrors.

What may not seem so clear, however, is exactly how magic functions rhetorically. The magic “act†may be nothing more than a simple sleight-of-hand or misdirection. Yet, many magic acts, or what Criss Angel calls “demonstrations,†are much more involved. They may be combined with other acts to produce illusions or altered perceptions of reality. These acts, then, are an art form that require years of practice and study. Whether it is a basic card trick or a Vegas-style illusion, the demonstration bends how one views the world.

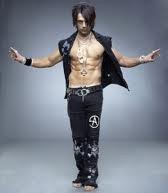

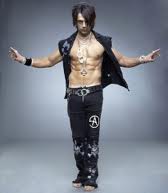

The art of magic has enjoyed increasing visibility and a resurgence of interest, as demonstrated by the rising popularity of magicians, such as David Blaine, Hans Klok, Franz Harary, David Copperfield, and the production of two major motion pictures within a single year – The Prestige (Nolan, 2006) and The Illusionist (Burger, 2006). With his number one-rated cable television show and his recent ten-year contract for a major Vegas show with Cirque de Soleil at the Luxor, Criss Angel personifies the modern-day magician who is at the forefront of the magic renaissance. He even argues in the first episode of Mindfreak that “magic today is not popular culture; I’m hoping to change that. Magic hasn’t garnered the respect as music or film, so that is what I’m trying to do increase its visibility with pop culture†(Angel, 2005a).

This paper attempts to examine the rhetorical potency of magic by analyzing the first season of Criss Angel’s award-winning television show, Mindfreak. In order to understand more clearly how the art of magic does this, I will use the Burkean concepts of symbolic action and identification to investigate how the meanings behind the symbols in magic function rhetorically. Since Burke remarks that “Words are the signs of things,†we shall investigate the signs behind the magic (Burke, 1966, p. 363). By looking at Mindfreak, I will focus on this connection between magic and rhetoric.

Review of Literature

The rhetorical dimension of magic has been relatively unexplored. In fact, most scholars have distanced themselves from studying magic because they deem it unsophisticated or non-academic. This distancing has its origins in antiquity. For example, the Hippocratic treatise, On the Sacred Disease, views magic as deceptive and contrasts it with the sacred principles of religion and piety (de Romilly, 1975, p. 27). The proclivity of associating magic more with religion and the occult than with the art of rhetoric is commonplace (Aune, 2003; Dunn, 2005; Kennedy, 1998; O’Keefe, 1982). In addition, Earle J. Coleman describes the lack of attention magic has received in most of the major disciplines, including psychology, sociology, history, and theatre (Coleman, 1987). Unfortunately, due to the inattention magic has received from the liberal arts, magic has been relatively unexplored as a serious art form.

Despite the sparse attention magic has received by scholars, some have discussed how magic and theatre have a strong relationship, especially since magic may be considered a performative art (Angel, 2007; Barnouw, 1981; Blaine, 2002; Fitzkee, 1944; Kennedy, 1998; Steinkraus, 1979). Furthermore, many have written about how magic is an art form, although its status as an “art form†is not associated, necessarily, with any particular academic area of study (Coleman, 1987; Dawes, 1979; de Romilly, 1975; Steinmeyer, 2003; Taylor, 1979). Even Burke, in A Rhetoric of Motives, refers to magic as an “art†(1969, p. 42). Although some consider magic to be an “art†form, most scholars overlook magic as an important component worthy of study, much less as a valued communicative act.

William Covino (1992) discusses the relationship between symbols and magic since antiquity, especially their simultaneous marginalization by so-called scientific reasoning. Elsewhere, Covino argues that magic is rhetorical in the sense that it is mysterious and that language has magical qualities (1994; 2002). However, he provides little support, other than his own perspectives, on the meaning-formation of magical acts. Nor does he explore how magic utilizes persuasive symbols. In an earlier work, Covino suggests that magic and rhetoric are synonymous, especially since the “congeniality of magic and technical rhetoric results from the real power of rhetoric to design and alter reality†(Covino, 1991, p. 25). In other words, Covino argues that language use in society borrows from principles of magic, especially regarding the generative capacity of language to portray collective or social ideas. In the end, while Covino makes the argument that magic and rhetoric are related, he emphasizes the magic in language, rather than the other way around.

In extending the assumption that there is some connection between rhetoric and magic, John O. Ward (1988) does a worthwhile job of chronicling the meanings given to rhetoric and magic. Tracing the historicity of both magic and rhetoric from ancient Greece and Rome to the Middle Ages, Ward argues that at different times, rhetoric is associated with magic, and at other times, rhetoric is seen as technȇ. In other words, at particular moments, the influence of magic can be seen in the conception of rhetoric, while at other times, rhetoric appears divorced from magical inspiration as it is viewed as purely instrumental in nature.

Perhaps the most important examination of both rhetoric and magic for our purposes occurs in de Romilly’s study, Magic and Rhetoric in Ancient Greece (1975). When examining The Gorgias and The Republic, de Romilly argues that rhetoric and magic are co-productive. In fact, she describes the relationship to the Greek concept of apatȇ:

Apatȇ, or illusion, is the aim of rhetoric. It is also the aim of magic, when the magician calls up phantoms and makes people believe in things that do not exist. That this is the very principle of rhetoric is obvious. An antilogy, where one speech opposes another, shows that it is possible to see in the same reality now one aspect and now another. Protagoras himself was proud of making the weak thesis strong, and the strong thesis weak. (p. 26-27)

While de Romilly sets up this relationship between magic and rhetoric, she does not expound on this argument (in fact, it only occurs in the span of two pages in the entire book), nor does she describe in any detail how magic has rhetorical implications or persuasive qualities. But, her reference of this relationship does help us by providing the foundation for analyzing the persuasive elements of magic. If magic and rhetoric share the concept of illusion in common, then we may begin our examination of Criss Angel’s demonstrations as rhetorical acts.

Burke, Symbolic Action and Identification

Before examining Criss Angel’s demonstrations to see what, if any, rhetorical connection exists with the art of magic, it will be helpful to briefly recall Kenneth Burke’s perspectives on symbolic action and identification. Burke’s important work on human symbol use centers on the foundation of how the meaning of language is not only shared among its users, but it also shapes the way those users think, feel, and express. Meaning, therefore, is central to the investigation of symbolic action (or the use of language) and identification (the manner and form taken to reach other symbol users).

For Burke, symbolic action deals with the way language reflects reality and shapes our perceptions of the world around us (Gusfield, 1989, p. 8). This happens, of course, because humans use language – or the meaning ascribed to the symbols used in language – to communicate their reality or perceptions of their world. The meaning of symbols is the focal point of all investigations into rhetorical acts (Gusfield, 1989, p. 6).  In fact, according to Gusfield, who edited the important work entitled Kenneth Burke: On Symbols and Society, “Language cannot be separated from action because what the action means and what it is addressed to is symbolic in its content. Action cannot be separated from language because the situation within which the actor acts is defined and understood by the actor through the concepts available to him [sic]†(1989, p. 11). Thus, Burke provides important insight into how the use of symbols shapes our perceptions – a key component to the art of magic. In terms of rhetoric, the meaning behind symbols is vital, since, as Burke describes, “Wherever there is persuasion, there is rhetoric. And wherever there is ‘meaning,’ there is ‘persuasion’†(1969, p. 172).

Additionally, Burke describes the process by which a symbol user attempts to reach, or persuade, other symbol users, or, for our purposes, an audience.   When discussing identification, Burke writes “A is not identical with his [sic] colleague, B. But insofar as their interests are joined, A is identified with B. Or he may identify himself with B, even when their interests are not joined, if he assumes that they are, or is persuaded to believe so. Here are ambiguities of substance. In being identified with B, A is ‘substantially one’ with a person other than himself. Yet at the same time he remains unique, an individual locus of motivesâ€Â (Emphasis in original, pp. 20-21). In other words, identification is a process that transcends persuasion, while it still uses persuasion to achieve its aim. Instead, identification is the moment when one person believes they fully share the perspective held by another. If I can convince my students to trust me as their instructor because I, too, was a student who sat in similar chairs they now sit in not too long ago, then I can identify with them and, perhaps more importantly for this example, they can identify with me.

To understand how magic functions rhetorically, we can use the concepts of symbolic action and identification to view how Criss Angel’s demonstrations resonate, as texts, with his audience. Burke actually speaks to this relationship, although he does not mention symbolic action specifically:

…one comes closer to the true state of affairs if one treats the socializing aspects of magic as a ‘primitive rhetoric’ than if one sees modern rhetoric simply as a ‘survival of primitive magic.’ For rhetoric is not rooted in any past condition of human society. It is rooted in an essential function of language itself, a function that is wholly realistic, and is continually born anew; the use of language as a symbolic means of inducing cooperation in beings that by nature respond to symbols (Emphasis in original, 1969, p. 43).

Furthermore, Burke briefly discusses the role of magic in a functional process of persuasion. Given magic’s persuasive aspects, the process by which this persuasion occurs might be considered identification:

The term ‘rhetoric’ is no substitute for ‘magic,’ ‘witchcraft,’ ‘socialization,’ ‘communication,’ and so on. But the term rhetoric designates a function which is present in the areas variously covered by those other terms. And we are asking only that this function be recognized for what it is: a linguistic function by nature as realistic as a proverb…For it is essentially a realism of the act: moral, persuasive – and acts are not ‘true’ and ‘false’ in the sense that the propositions of ‘scientific realism’ are. And however ‘false’ the ‘propositions’ of primitive magic may be, …it is different with the peculiarly rhetorical ingredient in magic, involving ways of identification that contribute variously to social cohesion (Burke, 1969, p. 44).

Thus, both symbolic action and identification serve to frame magic as a uniquely rhetorical, albeit persuasive, communicative art. Burke argues that magic, as a time-tested art practiced by primitive humans, is premised on the basic structures of language for it to operate. By examining a textual case study, such as Criss Angel’s Mindfreak, we should be able to see more clearly the rhetorical connection with magic.

Freakin’ The Mind: Examining Mindfreak

Criss Angel is fond of saying “what you see is what you get†(Angel, 2005a, 2005b, 2005c, 2005h). This, of course, is a double entendre, meaning it can be understood in two different ways. On one hand, he could be saying that what we visibly see is what is real (i.e., what you see is what you get). But, on the other hand, he could also be saying that whatever occurs visibly is what should be believed, meaning that whatever tricks occur within our vision should resonate with cognition (i.e., what you see is what you get). In fact, as one of Criss Angel’s consultants, Banachek, exclaims, “I think that people at home would be very surprised to find out that what they think might be illusion is actually reality, and what they think is reality, might actually be illusion. Criss is happy to blur that area, he wants people to wonder about what he’s doing. Because that makes good magic. If you’re asking questions, he’s doing his job†(Angel, 2005h). In the end, Criss Angel’s proclamation of “what you see is what you get†is nothing more than a disclaimer for added trickery for the audience.

Of course, this essay is not about how Criss Angel performs his demonstrations. It is not a manual on revealing the secrets behind the tricks. Instead, this essay concerns itself with how Criss Angel uses his demonstrations to persuade his audience. In other words, it concerns itself with the rhetorical strategies used by Criss Angel  to do the following: a) secure his audience’s attention, b) amaze his audience, and c) persuade his audience that his demonstrations are “magic.â€Â In so doing, this essay intends to suggest that magic is rhetorical, albeit persuasive. Magic, as exemplified by Criss Angel, is rhetorical since it engages in symbolic action and identification.

to do the following: a) secure his audience’s attention, b) amaze his audience, and c) persuade his audience that his demonstrations are “magic.â€Â In so doing, this essay intends to suggest that magic is rhetorical, albeit persuasive. Magic, as exemplified by Criss Angel, is rhetorical since it engages in symbolic action and identification.

Symbolic Action

According to Kenneth Burke, humans are “symbol-using, symbol-making, and symbol-misusing animal[s]†(Burke, 1966, p. 6; 1969, p. 33, 109, 237). As humans, magicians are no different. In fact, because magicians need to both entertain and amaze audiences, they are, perhaps, the most profound examples of human symbol-users. With each trick, or demonstration, magicians use symbols to convey their intention and purpose – namely, to mystify their audience. As such, Criss Angel does not disappoint. In numerous ways, he uses symbols – both verbal and nonverbal – to mystify his audiences. In this way, he uses symbolicity to enhance his magical prowess (Crable, 2003, p. 126).

In the different season one episodes of Mindfreak, Criss Angel displays numerous examples of symbolocity, or symbolic action. Whether through his explanations of his demonstrations or the demonstrations themselves, Criss Angel exemplifies the symbolicity of a rhetorical act. In essence, Criss Angel is trying to persuade his audiences that the demonstrations he engages in are real. As he is fond of saying, “What you see is what you get†(Angel, 2005a, 2005b, 2005c, 2005h). However, in many demonstrations, Angel fails to remind the audience that what they “see is what they get,†nor does he accentuate the importance of such a philosophy in each instance. Nevertheless, whether stated explicitly or not, Criss Angel’s demonstrations are typically viewed the way he presents them – i.e., as what he does is what we get. This means, of course, that some of the demonstrations seen on television may not be a part of Angel’s “what you see is what you get†mantra.

Consequently, Criss Angel uses symbolic action to highlight his demonstrations. Symbolic action “is the creation (or recreation) of an identity that fits into a culture … symbolic action involves the creation of an integrated world view (or recreation of a culture) and finding a place in that system. Such an accomplishment allows one to ‘feel at home,’ to size up situations, and to avoid epistemological crisis … symbolic action is any strategy for encompassing a situation†(McKercher, 1993). As such, Criss Angel uses particular symbols in certain situations to provide a certain perspective. Usually, the perspective involves ordinary situations that perplex the mind. As Criss is fond of saying, I like “to blur the lines of reality and illusion, I wanted to do a demonstration that would prove that the laws of this physical world can be bent or even broken†(Angel, 2005h).

If symbolic action is how language shapes our realities and perceptions, then many of Criss’s demonstrations do just that. For example, he uses symbolic action in episode two, “Levitation.â€Â It utilizes symbolicity, in part, because the idea of levitating connects with the audience. “The notion of being lighter than air is something that has intrigued every human being for hundreds and hundreds of years†(Kaufman, 2005a).  As Criss says, “I’m going to try to bug some people here in the park†and then he levitates himself in the park (2005b). One person in the audience says, “oh my God, how did he do that?â€Â The image of his levitation in a public setting creates the perception that he has mystical powers. There are no visible wires, no noticeable props, no apparent gimmicks. The demonstration appears real, although we know that there must be something to the trick. In fact, “It’s something that the street audience, the people who are right there and if you were there you’d see it too, take place in front of your very eyes†(Cohn, 2005).

In another episode, “Super Human,†Criss Angel engages in symbolic action by using symbolic images to create the perception that he has super-human strength. The finale demonstration has Criss lifting a taxi cab in Las Vegas. Before that, however, he asks several spectators on the street to line-up and consecutively push each other on the shoulders in an effort to push him over. Even with ten people (mostly burly men), they cannot push Criss over. One participant says, “It’s like pushing a wall†(Angel, 2005g). As he ambiguously explains the process, Criss says, “your mind controls your body, and what doesn’t make sense to some people makes sense to others†(Angel, 2005g). The image of him lifting a taxi also creates the perception that his super-human strength is a reality, hence symbolic action. Criss explains, “I wanted to accomplish something that looked to be completely impossible for someone with my weight to be able to do and hopefully that demonstration will inspire others to be able to fulfill their dreams that might seem impossible at that very moment†(Angel, 2005g). This is important, as Criss indicates, since “If you dream it, you can achieve it,†and later he says, “I’m committed to do things that people don’t think are possible†(Angel, 2005g).

Symbolic action, as has already been described, is a process by which we look at language to inform us of meanings laden within the linguistic code. In other words, it is the process we use to ascertain meaning in the complex symbol-using process. What we understand may or may not be a simple perceptual process of the conglomeration of signs.

As such, the symbolic action expressed in Criss Angel’s demonstrations reveals that magic utilizes symbols. Whether it is words or nonverbal gestures, the magician incorporates symbols for his/her ultimate effect. Of course, the magician also needs to manipulate the audience’s perception of the symbolic context around them. As Criss Angel suggests, “An illusion exploits the way you visually process something†(Angel, 2007, p. 158). This is particularly true since magic is the “audacious individual use of existing powerful symbols†(O’Keefe, 1982, p. 73). In other words, the symbols used in an illusion are merely a distraction so that the ultimate symbol(s) – the climax of the illusion – demonstrate the importance of a perception of reality. As Burke posits, “Even if any given terminology is a reflection of reality, by its very nature as a terminology it must be a selection of reality; and to this extent it must function as a deflection of reality†(Burke, 1966, p. 45). Hence, magic, if done properly, is merely a deflection of reality, and, as such, is only a symbolic perception of one’s (i.e., audience member’s) conception of reality.

Identification

Criss Angel uses identification in the first episode in season one of Mindfreak. Criss, who seemingly is being burned on Freemont Street (one of the busiest streets in Las Vegas), lies down on the pavement after being burned for over 30 seconds, and then the body disappears and we see Criss as one of the aids who is using a fire extinguisher to put out the fire. He replaces the victim with the rescuer. As Criss states, “I like to play with what people’s fears are; I like to confront those for people, and people have a fear of being burned alive†(2005a).

This is a sentiment that we hear as well in a later episode, called “Building Walk,†where Criss walks down 50 stories of the Aladdin hotel to confront the fear of heights (Angel, 2005h).

A second example of identification occurs in the fourth episode, entitled “SUV Nail Bed.â€Â The show, among other things, focuses on Criss lying on a bed of eight-inch nails while an SUV is slowly driven over him. During the commentary leading up to the stunt, Criss says, “I don’t think of pain as most people would probably perceive it … Pain is beautiful thing, when you feel pain, you know you’re alive†(Angel, 2005d). A little later he says, “Pain is just something that you can overcome†(Angel, 2005d). The idea that he endures pain as a form of identifying with his audience seems apparent enough. Before the SUV demonstration, Criss approaches some folks on the street. He then swallows needles and thread and then pulls them out of his belly button. The crowd makes comments such as “oh my god,†“oh God that’s crazy,†“that was nuts,†and “I’m freaked out†(Angel, 2005d). The perceived physical act of pulling needles through one’s flesh clearly illustrates the endurance of pain. Taking it to another level, the SUV nail demonstration heightens the perception of conquering pain. As Criss states toward the end of the show, “Failing equals death, so I have no margin for error†(Angel, 2005d).

In another episode, the “Wine Barrel Escape,†Criss Angel is essentially paying an homage to Harry Houdini since he will be padlocked in a wine barrel several stories in the air. As he prepares for the demonstration, Criss Angel tells the audience that the water is too cold and his muscles couldn’t function, so he asks for warmer water. Lance Burton, who is narrating this episode, says this “isn’t the stunt to try when you don’t have full control of your body†(Burton, 2005).  This all adds to the suspense of the demonstration. And, to add to the suspense even more, after they initially raise the wine barrel, they bring it down after Criss gave the “abort†signal because, as he says, “a line got caught†which made his wrists get “crushed†(Angel, 2005c). Lance Burton says this is incredible because Criss Angel had the “presence of mind†to make the call (Burton, 2005). This helps the identification with the audience, as it did in Houdini’s day, because it resonates with the audience’s perception of fear. As Criss Angel states, “Houdini had this profound effect on people because he connected to them on an emotional level†(Angel, 2005c). As such, Criss Angel, too, impacts the audience on an emotional, albeit fearful, level.

In another episode, “Buried Alive,†Criss Angel is literally placed into a coffin and buried six-feet under. Criss remarks, “We’re going to actually have a POV camera in there so that people at home can actually experience what it feels like to be buried alive†(Angel, 2005e). Like his other shows, Criss portrays the conquering of basic fears. Scholars have documented that being buried alive is one of the most basic and dreaded of all fears (Bondeson, 2001).  In this way, Criss Angel is identifying with his audience on a very primal level. As Banachek, a Mindfreak consultant and accomplished mentalist, remarks, “If something goes wrong, he’s definitely dead†(Banachek, 2005a). Thus, the fear of dying, especially by being buried alive, triggers an emotional response from the audience.

In two different episodes – “Hellstromism†and “Blind†– Criss Angel demonstrates that muscle and mind reading are crucial to everyday activities of a magician. In “Hellstromism,†Criss needs to locate certain objects through the touch of a participant who knows where the objects exist. In “Blind,†Criss relies on Mandi Moore to help him drive a car blind-folded. Of course, he also asks her to think of a place in Los Angeles, without his knowledge, and he drives the car to that location. In “Hellstromism,†Criss argues that “Muscle reading is basically the ability to actually determine what’s somebody’s thinking by the way their muscles are reacting†(Angel, 2005f). Later in the episode, noted Mindfreak consultant and Criss Angel friend, Banachk suggests, “A mentalist is somebody who performs magic of the mind, we appear to be psychic, we appear to move objects, read people’s minds, who really get into people’s minds†(Banachek, 2005b, “Predictionâ€). As a result, as Banachek suggests in a different episode, “the skill of getting into people’s heads is tricky. It’s so hard, and he has a natural ability. Creating that vulnerable moment for people so that they really think you’re getting into their head, allows you to truly get into their heads†(Banachek, 2005c). Thus, Criss Angel uses his powers of mental manipulation to identify with his audience. By claiming to be able to read people’s minds, Criss provides the perception that he has unique powers that enable him to understand the condition of other people. This is, perhaps, the quintessence of identification.

As in some of his other shows, Criss Angel uses his illusion of walking down 50 stories of the Aladdin hotel/casino as a demonstration of his ability to conquer another fear – the fear of heights. In “Building Walk,†Criss literally is shown as walking down the building of the Aladdin. In one way, this is a form of identification because many people dream to walk up or down a building – much like Spiderman. As Dale Hindman, the president of the Magic Castle, suggests, “Criss is doing what Harry Houdini did. Know that that’s what your audiences want, and then go after them with a vengeance and make it public, and do it better than the next guy. Harry Houdini did that all the time†(Hindman, 2005). On the other hand, Criss is identifying with his audience, yet again, by confronting a fear – in this case, the fear of heights. According to Criss, “With ‘Building Walk’ specifically, I try to address people’s fears. What I’m trying to do is overcome other people’s fears, and hopefully they’ll get the ‘how the hell did he do that’ factor in there†(Angel, 2005h). In a related way, Richard Kaufman, the publisher of Genii magazine, argues, “most people don’t like to dangerous things themselves, but they like to watch other people do dangerous things. There’s that aspect of voyeurism that people find intriguing†(Kaufman, 2005b). Yet again, Criss is identifying with the audience because his demonstration deals with a common human fear. As he claims in the episode, “I think when you confront your fears, you grow as a person. People everyday don’t live life to its fullest because they’re concerned about getting on planes, they can’t get out of their house, they can’t go on an elevator – they’re so many things that people fear. So, for me if I can help one person to live their life to the fullest, that means a lot to me†(Angel, 2005h).

Once again, in “Blind,†Criss Angel confronts people’s fears of sensory deprivation. With taped coins around his eyes in addition to a solid black blindfold, Criss drives Mandi Moore’s care through Los Angeles to a destination of her choosing, but without his knowledge (Angel, 2005i). Luke Jermay, a Mindfreak consultant, argues, “I don’t believe Criss is psychic; I believe he’s a very skilled performer with a toolbox of techniques that he uses to produce the illusions that he does†(Jermay, 2005). Nevertheless, even if Criss Angel does not possess mystical powers, his ability to navigate through crisis situations, while appearing to be blind, yet again resonates with the audience who fears losing their own sight. In this way, Criss identifies with his audience, by means of his own magical demonstrations, in a way that signals his unique abilities that transcend the common person’s basic fears.

As we have seen, Criss Angel attempts to draw his audience into his demonstrations. Whether it is in the street or on a more massive demonstration of an illusion, Criss Angel tries to bring his audience into his artistic creation. As Criss stipulates in his book, “When I perform, I use my power, my gifts, my art to help people escape from the ordinary into the world of the extraordinary. I have the power to help them forget their problems, if only for a few moments†(Angel, 2007, p. 149). The point, of course, is not only to identify with one’s audience, but also to connect with them on a basic, emotional level. Criss agues that he is able “to take people to places they would never otherwise experience. The emotional connection is like a passageway to a private world – my private world. Fantasy and the great unknown have always fascinated people … The wonderment, the unexpected, the moment of ‘wow’ is something I live for†(Angel, 2007, p. 126). Of course, the “amazement†factor is only part of the equation. Criss Angel, undoubtedly, wants to “wow†his audience. However, like most magicians, Criss Angel is also concerned with identifying with the audience in a special, unique way. For Angel, this connection entails a purpose that signifies that a single person can overcome a particular hardship. Much like Houdini, Criss Angel tries to overcome the constraints that many people feel that oppress them. In fact, as Criss argues, “I loved Houdini’s primary message. If I can get out of this situation, you can get out of yours†(Angel, 2007, p. 89). In this way, Criss Angel identifies with his audience in a very important way – he exemplifies the ability to overcome hardship and tribulation. The capacity to conquer fears and fortitudes is a magician’s sign that he/she is able to transcend the average conundrum. As a result, they signify that anyone, including the common person, can overcome such difficulties themselves.

Conclusions

Criss Angel provides us a unique opportunity to see how magic and rhetoric intersect. While not revealing any of his magic secrets, this essay acknowledges Angel’s hard work and unique magical abilities – both on-screen and off. Furthermore, this paper identifies several different ways that magic is rhetorical. In some ways, the magical performance is magical in the way it is performed (Steinmeyer, 2003). In other ways, the words the magician uses while performing the act are important (Angel, 2007; Covino, 1992; Steinmeyer, 2003). In any case, the “trick†or “act†itself in magic is persuasive since it captivates the audience’s attention and convinces them that the trick or act is part of reality.

What is illusion and what is “real†is open to debate. That is the magician’s trade – to blur reality with illusion. According to Paul Draper, a former consultant to Criss Angel’s Mindfreak, “Magicians provide physical and tangible representations of the miraculous that fools all of our senses. Audiences can take many meanings from this to fit their personal needs and beliefs†(Draper, 2007). Thus, conjurer’s use the skills of the trade to convince the audience that what is impossible is possible, what is unrealistic is real.

Given the paucity of studies that examine the intersection between rhetoric and magic, this paper treads new territory. It also provides an opportunity for those interested in the art of magic and the art of rhetoric to see how both can mutually reinforce the other. And this is really the beauty of a study like this – both objects of analysis can reinforce the other. In essence, the rhetorical possibilities as well as the rhetorical prowess of magic can illuminate not only the essence of persuasion, but also the practical effects of symbolic influence.

Of course, much more investigation can occur regarding the relationship between magic and Burke. While Burke argues that that magic is, at least in some ways, rhetorical, he never goes so far as to suggest the manner or methods in which magic is rhetorical. However, for our purposes, Burke could prove to be instrumental in additional rhetorical studies. As he says, “By the ‘symbolic’ or ‘sympotmatic’ nature of terms (in the strictly psychoanalytic sense) we mean their significance, not as defined in a sheerly lexical context (as in a dictionary) but as secretly infused with some ‘repressed’ or ‘forgotten’ context of situation that was in some way ‘traumatic’†(Burke, 1966, p. 359). We could argue that magic is one of those situations. At the very least, the performative art of magic could be the “nature†or “situation†of rhetorical action. In this way, Burke offers us the possibility of future research in the area of magic and rhetoric.

Based on Criss Angel, I believe we can make the argument that magic is rhetorical – it uses symbols and images to frame our sense of reality based on illusion, it embraces symbols to identify with us as the audience, and it persuades us that what is occurring is real. What is central to this discussion is the intersection of image and meaning. While we haven’t described in much detail the importance of message or meaning in this discussion, we cannot, nevertheless, overlook it. As Burke describes, “meaning and symbol are not dependent as things on context; they are relations, not objects. Ignoring this point, seeing meaning and symbols as things ,has allowed cultural analysts to erect a distinction between symbolic structures and concrete structures; to differentiate religion, myth, art – held to be “essentially†symbolic forms – from economics, politics, kinship, or everyday living†(Gusfield & Michalowicz, 1984, p. 418).  This is even more pronounced when we see what David Devant – the notable magician of the turn of the century of the 1900s – argues that, “I regard a conjurer as a man who can hold the attention of his audience by telling them the most impossible fairy tales, and by persuading them into believing that those stories are true by illustrating them with his hands, or with any object that may be suitable for the purpose†(Emphasis added, David Devant, quoted by Steinmeyer, 2003, p. 93). Therefore, the magician uses their talents to connect with the audience. In fact, it is crucial that the magician does so in order to relate to the audience in a manner that resonates with the audience in a key way to connect them with the acts on the stage or on television. In essence, then, “Magic is a social act whose medium is persuasive discourse, and so it must entail the complexities of social interaction, invention, communication, and composition†(Covino, 1992, p. 363).

While magic is rearing its ugly head in movies like The Prestige and The Illusionist, we also see its attraction in performing artists like David Blaine, Hans Klok, and Franz Harary. Of course, there is also Criss Angel. As Lance Burton suggests, “Criss [Angel] is going to be written in the history books as one of the great magicians in the 21st century†(Lance Burton, 2005). This may be true, but any good magician or illusionist must understand their audience. Jim Steinmeyer, one of the most notable and respectable magic historians and trick architects, claims, “When magicians are good at their jobs, it is because they anticipate the way an audience thinks. They are able to suggest a series of clues that guide the audience to the deception. Great magicians don’t leave the audience’s though patterns to chance; they depend on the audience’s bringing something to the table – preconceptions or assumptions that can be naturally exploited†(Steinmeyer, 2003, p. 117). Therefore, the audience is key. And persuading the audience is central to a magician’s purpose.

References

Angel, C. (2005a). Burned alive. Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Angel, C. (2005b). Levitation. Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Angel, C. (2005c). Wine barrel escape. Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Angel, C. (2005d). SUV nail bed. Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Angel, C. (2005e). Buried alive. Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Angel, C. (2005f). Hellstromism. Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Angel, C. (2005g). Super human. Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Angel, C. (2005h). Building walk. Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Angel, C. (2005i). Blind. Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Angel, C. (2007). Mindfreak: Secret revelations. New York: Harper Collins.

Aristotle (1991). Aristotle on rhetoric: A theory of civic discourse (edited and translated by G. A.

Kennedy). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Aune, J. A. (2003). Witchcraft as symbolic action in early Modern Europe and America.

Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 6, 765-777.

Banachek (2005a). In Criss Angel’s “Buried Alive.†Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Banachek (2005b). In Criss Angel’s “Prediction.†Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Banachek (2005c). In Criss Angel’s “Blind.†Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Banachek (2005d). In Criss Angel’s “Building Walk.†Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Barnouw, E. (1981). The magician and the cinema. New York: Oxford University Press.

Black, E. (1992). Rhetorical questions: Studies of public discourse. Chicago: University of

Chicago Press.

Blaine, D. (2002). Mysterious stranger: A book of magic. New York: Villard.

Bondeson, J. (2001). Buried alive: The terrifying history of our most primal fear. New York:Â Norton & Company.

Burger, Neil (director) (2006). The illusionist. Yari Film Group.

Burke, K. (1966). Language as symbolic action: Essays on life, literature, and method.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Burke, K. (1969). A rhetoric of motives. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Burton, L. (2005). In Criss Angel’s “Wine Barrel Escape.†Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Cohn, R. (2005). In Criss Angel’s “Levitation.†Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Coleman, E. J. (1987). Magic: A Reference Guide. New York: Greenwood Press.

Covino, W. A. (1991). Magic, Literacy, and the National Enquirer. In Patricia Harkin and John

Schilb (Eds.), Contending with words: Composition and rhetoric in a postmodern age. New York: The Modern Language Association of America.

Covino, W. A. (1992). Magic and/as rhetoric: Outlines of a history of phantasy. JAC, 12.2,

available via Ebsco Academic Search Premier.

Covino, W. A. (1994). Magic, rhetoric, and literacy: An eccentric history of the composing imagination. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Covino, W. A. (2002). The eternal return of magic-rhetoric: Carnak counts ballots. Rhetoric and composition as intellectual work (ed. by Gary A. Olson). Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Crable, B. (2006). Symbolizing motion: Burke’s dialectic and rhetoric of the body. Rhetoric Review, 22, 121-137.

Dawes, E. A (1979). The great illusionists. Secaucus, NJ: Chartwell Books.

de Romilly, J. (1975). Magic and rhetoric in ancient Greece. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Devant, D. (1909). Magic made easy. London: Cassell.

Draper, P. (2007, September 17). Personal Interview.

Dunn, P. (2005). Postmodern magic: The art of magic in the information age. St. Paul:

Llewellyn Publications.

Fitzkee, D. (1944). The trick brain. San Rafael, CA: St. Raphael House.

Giobbi, R. (2007, April). Artistic magic. Genii: The conjurors’ magazine, 70, 20-23.

Gusfield, J. R., & Michalowica, J. (1984). Secular symbolism: Studies of ritual, ceremony, and the symbolic order in modern life. Annual Review of Sociology, 10, 417-435.

Hindman, D. (2005). In Criss Angel’s “Building Walk.†Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Jermay, L. (2005). In Criss Angel’s “Blind.†Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Kaufman, R. (2005a). In Criss Angel’s “Levitation.†Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Kaufman, R. (2005b). In Criss Angel’s “Building Walk.†Mindfreak: Season One. A&E.

Kennedy, G. A. (1998). Comparative rhetoric: An historical and cross-cultural introduction. New York: Oxford University Press.

McKercher, P.  (1993) Toward a systematic theory of symbolic action. Ph.D. dissertation.

University of British Columbia. Available online: https://people.ucsc.edu/~pmmckerc/D11.HTM.

Nolan, Christopher (director) (2006). The prestige. Newmarket Productions.

O’Keefe, D. L. (1982). Stolen lightning: The social theory of magic. New York: Continuum.

Ortiz, D. (2007, April). Designing miracles. Genii: The conjurors’ magazine, 70, 93-94.

Raven, M. (2007, November). Max Raven and the evolution of a mind reader. Genii: The

conjurors’ magazine, 70, 50-68.

Steinkraus, Warren E. (1979, October). The art of conjuring. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 13, 17-27.

Steinmeyer, J. (2003). Hiding the elephant: How magicians invented the impossible and learned to disappear. New York: Carroll & Graf.

Steinmeyer, J. (2007, November). Max Raven and the evolution of a mind reader. Genii: The conjurors’ magazine, 70, 50-68.

Taylor, A. (1979). Magic and English romanticism. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Ward, J. O. (1988). Magic and rhetoric from antiquity to the renaissance: Some ruminations. Rhetorica, 6, 57-118.